Coloniality Encounters: Ballet

Ever since I started engaging with the study of coloniality

and the whole decolonial movement, including thinkers such as Walter Mignolo, my eyes

are being opened to how coloniality played in my own life. Pulling together a series of anecdotes that

reflect my own lived experience. This is the first.

Ballet

Born into an elitist anglicised and Christian Ceylonese

family I grew up in that rarefied bubble that was Colombo society, oblivious to

how our colonial history had shaped my life and those around me. At my

grandparents’ extended family home in Cinnamon gardens, we spoke English among the

family, and in Sinhala to the servants, though I do have an early recollection

of Isabel Nanny who conversed with me in English. She always wore a soft white osariya that

contrasted starkly with her dark skin but that is as much as I can recall of

her. She was the exception. In the servants quarters (where admittedly I

as the only child in the house spent a lot of my time) the lingua franca was

Sinhala.

My Daddy Seeya (paternal grandfather), a big jolly man,

retired civil servant, senator and Scout Commissioner, would have preferred me

to talk more in Sinhala, which I then thought was quite eccentric. I remember being quite annoyed when he found

my autograph album and wrote a verse in it in Sinhala. As his eldest

grandchild I was spoiled rotten by him, but he also sought to bring me

down to earth. “We maybe in this big

house now” he’d say to me in Sinhala “ but you mustn’t forget that our families

are really cattle thieves from Bandaragama!” He’d chuckle a little to himself and add with a twinkle “actually,

we didn’t steal the cattle, we just ate the cattle that the (a well known Sinhala family) stole!”

My Mummy Seeya (maternal grandfather) was a completely different kettle of fish. Diminutive and a lot more serious than Daddy

Seeya, I was surprised to learn that they had known each other and actually

been friends while in the Ceylon civil

service. Mummy Seeya had an impressive

record of service to the country, having worked with D S Senanayake on securing

independence from the British, knighted Sir Arthur by Her Majesty Queen

Elizabeth II on her visit to Ceylon, and then serving as the Governor of the

Central Bank and our Ambassador to Rome.

He retired to Kandy, and we spent many of our school holidays at his home.

It is instructive that despite his role in securing independence for Ceylon (as

Sri Lanka was then known), Mummy Seeya seemed to me very British. He had an impeccable command of the English

language, he always used cutlery at mealtimes, and he always dressed for

dinner! I was quite intimidated by him

and generally tried to keep out of his way. It is

unsurprising then that he was the first

person to deliver a blow to my emerging awareness of my own non-British culture

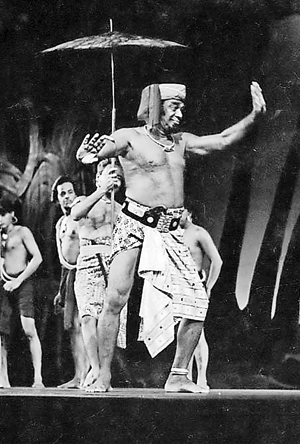

I must have been a teenager, or a little younger, when I saw Chitrasena

perform Karadiya at the Lionel Wendt Theatre.

I cannot remember who took me there, but I do remember being completely

transfixed by the powerful performance, the beauty of the dance and the

poignancy of the narrative. I had only

seen traditional dances at the Kandy Perahera and occasionally at variety

performances of low country dance forms, though none of this had really

penetrated my consciousness. True to my

Anglophilic upbringing I had also seen films (we had no television at that

time) of Western Ballets such as Swan Lake or the Nutcracker and been to the

inevitable concerts of local western ballet schools. I remember as a child being sent to a Kandyan dancing class at the Cultural Centre down what was then, General Lakes Road (now Sri James Pieris Mawatha) but I winged so much that my mother gave in and let me discontinue that extracurricular activity - a decision I regret to this day.

I had no recognition then of Chitrasena’s genius nor of his

pioneering work transforming traditional dance forms from their historic

ritualistic positioning into theatrical and narrative performances. I just witnessed an evocative and beautiful

spectacle that resonated with my whole young self. I was not aware that cultural

history was being made. In his article on the 100th Anniversary of

Chitrasena’s birth in 2021, Chitrasena’s

Mudra Natya: Embodying the form Mirak Raheem quotes cultural critic and

commentator Neville Weeraratne saying how in Karadiya, Chitrasena “ did

something wonderful. He created a

dance-theatre unique to the traditions of Sri Lanka, and indeed, to the

experience of many parts of the world… Karadiya was the first complete

ballet, combining elements of the dance as known and recognisably Sri Lankan in

character and a highly articulate language of mime and gesture, wrought and

subject to the needs of the narrative.”

So with the drumming still reverberating

in my ears and a not quite formed aesthetic sense heightened by the beauty of the dance and the

romance of the story, on my next trip to Kandy probably quite

soon after seeing Karadiya, I remember recounting to my mother, Mummy Seeya,

and others who were there my delight at witnessing this performance. And I remember saying that it was a really such a beautiful ballet, at which point Sir Arthur intervened with a quiet authority seeped in coloniality:

“THAT is NOT ballet” he declared firmly and that was that.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment