Where were the women?

It’s been 70 years since the Bandung Conference brought leaders of Asian and African countries together in a collective effort to forefront anti-colonial and anti-imperial struggles. Twenty-nine Asian and African countries attended and the 1955 conference symbolised a ‘new spirit of solidarity of the Third World’ . The conference underscored two principles of Third World politics – decolonisation and development – and led to the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and an alternative conversation on how the world should be ordered including a proposal for a New International Economic Order (NIEO). It was a time when Sri Lanka punched significantly above her weight – Mrs Sirimavo Bandaranaike was an acknowledged leader of NAM, Dr Gamani Corea pushed for more favourable trade terms for the global south from his position as the Secretary of UNCTAD, and Ambassador Shirley Amerasinghe pushed against international competition to acquire the resources of the sea bed and was a key player in the International Law of the Sea conferences. It was a time when the themes of the Bandung conference, economic cooperation, respect for fundamental human rights and the principles of the UN Charter, promotion of world peace and recognition of the equality of all races and the equality of all nations large and small, framed the discussions between nations.

Today we live in a world that is experiencing economic, ecological and geo-political crises, and where the above themes of Bandung have been sidelined if not completely obliterated. Many global south countries are deeply entrenched in debt, world peace is wilfully ignored, and genocidal actions and structural violence proliferate from Burma to Palestine. It is also a world in which limiting global warming to 1.5° Celsius is no longer possible and the consequences of climate change presents an existential crisis. It is a time where the revival of the “Bandung spirit” should provide a resonance that can inspire and inform the foreign policies and international relations of small states like Sri Lanka.

Here I ask the question famously raised by Cynthia Enloe in her writings on international relations –where were the women? It seems like there were NO female delegates at the conference . And even though the 10 points of the Bandung Declaration reiterated the principles of the UN Charter and set a standard for international relations’ and that championed coexistence instead of co-destruction, it did not explicitly refer to women’s rights. Neither this lack of representation nor the omission of women’s rights from the agenda or outcome of the conference meant that women were missing from anti-colonial and anti-imperial struggles that underscored the Bandung spirit – far from it.

In the first half of the 20th century, starting before Bandung, different constellations of national and international women’s organisations planned and implemented three conferences that foreshadowed the rise of women’s international solidarity in Asia and Africa and could have, as some commentators have argued, informed the emerging pan-Asian and Afro-Asian movement for anti-imperialist regional cooperation symbolized by Bandung.

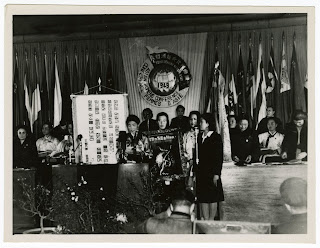

In 1949 the Conference of the Women of Asia was held in Beijing, China, hosted by the Women’s International Democratic Federation (WIDF) together with the All-China Women’s Democratic Federation and Mahila Atma Rakshi Samiti (MARS) or Women’s Self-Defense Committee from West Bengal, India; in 1958 the Asian-African Conference of Women was held in Colombo, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), under the aegis of five national women’s organizations from Indonesia, India, Pakistan, Burma, and Sri Lanka; and in 1961 Afro-Asian Women’s Conference was held in Cairo, Egypt, organized by the Afro-Asian Peoples’ Solidarity Organization (AAPSO) with strong support from the Non-Aligned Movement, including Gamel Abdel Nasser’s government in Egypt.

Not only did the 1949 conference precede Bandung but it took place well before the now familiar United Nations World Conferences on Women, the first of which was held in Mexico City in 1975 ushering in the UN Decade for Women. The early 20th century gatherings of women from Africa and Asia were the outcome of what was a long-standing critique by women from the colonised countries of Western feminism and the development of solidarity along common issues faced by women in the global south

There were several strands to the agenda and demands of global south women at this point in history. A social reform agenda demanded better access for women to education, health care, and social welfare and sought to “modernise” cultural and religious practices. In some ways this agenda mirrored the agitation by nationalist reformers in societies that were demanding decolonisation who saw education and freedom for women, and monogamy, as markers of modernity and development, They strived to create the “enlightened” woman, a partner for the “bourgeois man”, who negated everything that was considered ‘backward’ in the traditions of the colonised societies. The concept of the “new woman” became eagerly adopted, albeit with regional variations, from Egypt to Japan, China to Korea While the ‘new woman’ image at one level reflected characteristics of the emancipated women of Europe and the USA, and the demand for education allowed women from the bourgeois classes to come out of their homes and into various professions and social work, there was also an underlying conservative emphasis on traditional ideals of the woman as wife and mother, reinforcing women’s role as care givers despite the quest for legal equality.

A second strand of feminist agitation In the early 20th century comprised a nationalist and state agenda that sought equal rights for women in independent nations and women’s full participation in public life. As women became more educated their demands also stretched to obtaining voting rights. This agitation was fuelled as the growing feminist literature of the women’s movement (books, journals and magazines) began catering to the educated and literate ‘new’ woman and reported the efforts for women’s emancipation in different parts of the world. So women in Asia and Africa were able to access information about suffragist and feminist struggles in Europe and by the early decades of the 20th century women in China, India, Japan and Sri Lanka were agitating for women’s suffrage in their countries, organising demonstrations and storming the legislature when voting rights were not granted.

What has received the least attention however in the historic accounts has been that strand of feminist organising that sought to restructure the economy as well as social relations and cultural and political practices to enfranchise all women. These feminist movements tended to push their change agenda beyond the nationalist struggles even after formal independence was granted. They recognised that economic pressures from imperial powers and the national propertied classes and business lobbies weakened the political will of governments to institute reforms. Colonial forms of ownership of the means of production continued under the new decolonised systems. They mobilised peasant women and landless migrants in urban areas with the aim of building a movement led by rural, peasant, working class and middle class women. Their activism was based on anti-imperialism, mass-based organising, a membership dominated by rural women and anti-capitalism. It was this strand of feminist analysis and thinking that dominated the first of the international conferences that was held in Beijing in 1949. Some commentators have argued that this ideological stance of the first pan-Asian women’s conference informed the emerging pan-Asian and Afro-Asian movement for anti-imperialist regional cooperation symbolized by Bandung.

However that might be, the spirit of Bandung that was embodied in the 1949 Conference and the women’s organisations that were instrumental in making it happen, have some significant lessons for feminist organising in today’s world. Women today are faced with a human rights and development discourse that has for too long been dominated by cis white men from the global north and which has inadequately incorporated the expertise, experience, priorities and perspectives of women and other marginalised groups in the global south. The emerging discussions on decoloniality and decolonisation are in danger of being coopted by a certain brand of white feminism, there is a real pushback on the rights of women, sexual minorities and other marginalised groups, and international solidarity among the different women’s movements are constrained by geopolitical concerns and fear.

In this context, Elizabeth Armstrong’s description of the internationalist solidarity of the women’s movement in the early 20th century as “a solidarity of commonalty for women’s shared human rights, and a solidarity of complicity that took imbalances of power between women of the world into account” is particularly relevant and inspiring. A solidarity for a commonalty of women’s shared human rights is what feminists today would describe as ‘intersectionality’ – or the recognition of effects of multiple forms of discrimination on women’s daily lives; understanding how various aspects of individual identity such as race, gender, social class and sexuality, interact to create unique experiences of privilege or oppression. For the women at the 1949 conference in Beijing, mobilising peasant women and agricultural workers, as well as landless urban workers resulted in advocacy against unequal wages, inadequate health systems, food sovereignty, debt, trafficking of women and girls, gendered caste practices and landowners’ control over the agricultural products of peasant and agricultural workers labour. In doing this they challenged the class structure of the agricultural economy and the endemic inequities of the capitalist class system. They also demanded from the colonial or newly independent state, better resources for poor, working class and middle-class women. Their coalitional campaigns for universalised human rights included women’s political, economic, social and cultural rights that invoked shared values and goals that would benefit ALL women everywhere.

In the 1940s the geo-political area that comprised “Asia” included West Asian countries like Lebanon and Syria as well as parts of North Africa, like Morocco, Algeria, and Egypt and the women’s movement in Asia and Africa was strengthened by the anti-imperialist, anti-fascist energies of women’s activism in these countries. Particularly energising was the pan-Arab women’s movement sharpened by the issue of Palestine and the formation of Israel. As such, the solidarity of complicity that was displayed by the women’s movement of the time took responsibility for acts of oppression and discrimination carried out in their nation’s name or by their nation’s people. For example, Indian women condemned the British government’s use of Indian troops to squash the independence movement in Indonesia and Vietnamese women appealed to their African sisters to protest against the sending of Algerian, Moroccan, Tunisian and Senagalese soldiers to Vietnam.

In the words of Roeslan Abdulgani (1914–2005), the secretary-general of the Bandung Conference

The Bandung Spirit was the voice of the hundreds of millions who had lived under colonial rule and who spoke against the horrors of colonialism as well as their hope for a new world.

Today, 70 years later, hundreds of millions of women, men and children continue to live in an equally horrendous world. It is a world plagued with debt; where smaller, weaker states are subject to a world order that is dominated by the dictates of international financial institutions on everything from the economy to governance, development and social welfare; and where the idea of world peace has been wilfully abrogated by the powerful. However, as the mood in Asia and other parts of the global south swings towards the possibility of once more working towards democratising the world order and reviving the Bandung spirit, it would seem that women are still missing from the conversations. It is imperative we do better this time round. That we do not omit the women and that we instead build on the ideas of international solidarity of commonalty and complicity that were displayed by the women’s anti-imperialist movements of the early twentieth century.

This article was first published in the Island Newspaper on June 2 and 3rd.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment